Introduction of virtual element method (VEM)

VEM is a recently proposed numerical discretization technique in Galerkin framework which is inspired by mimic finite difference (MFD) method, and since the date of birth it has been extensively developed and applied to a wide range of engineering problems. The core of the method is to construct a projector which projects the function in local virtual element space (or say, local shape function space) to a polynomial space with prescribed order. In this way VEM avoids the explicit construction of shape function and its integral over the element domain; and thus VEM is able to handle arbitrary polygonal mesh.

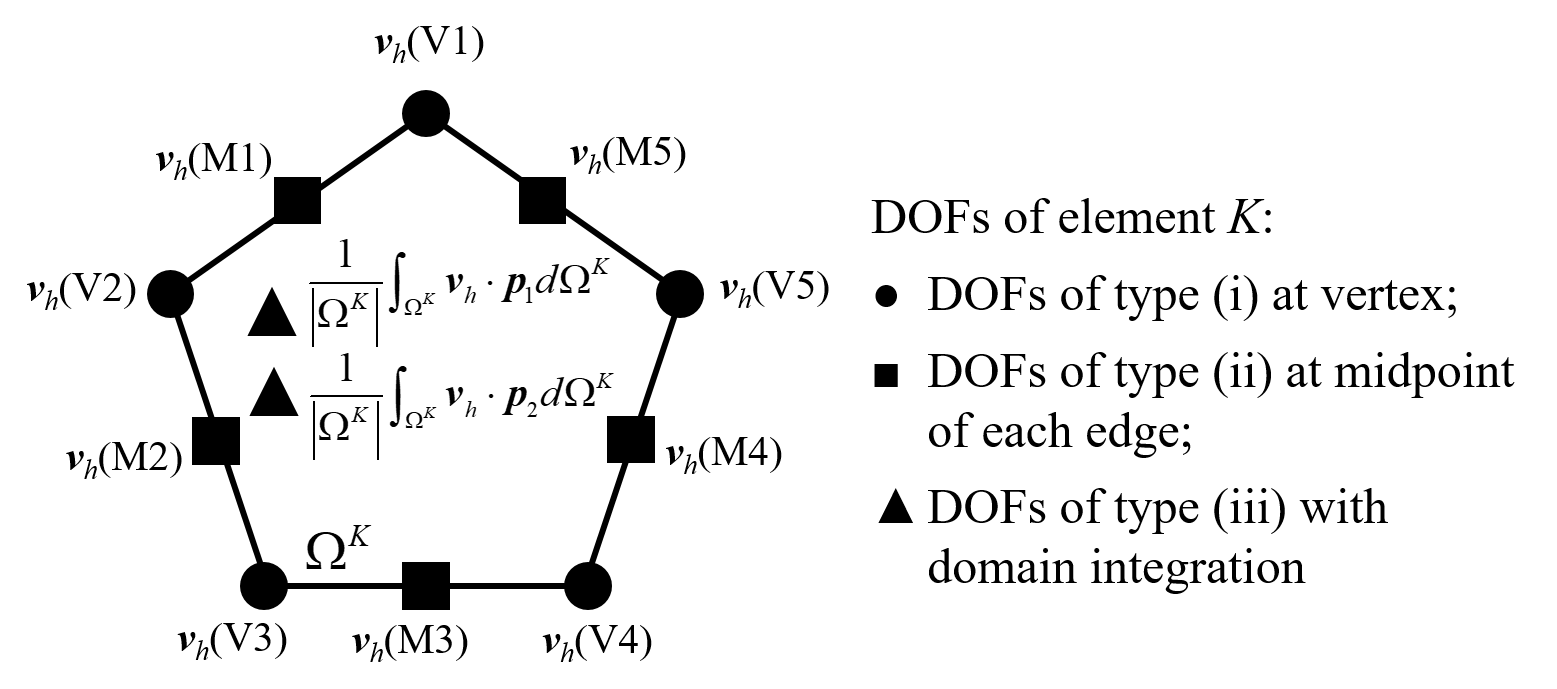

In order to give a simple and general illustration of how VEM works, here I take a linear elasticity boundary value problem in 2-dimensional domain $ \boldsymbol\Omega $ as example. The domain is partitioned into arbitrary polygonal meshes $T_h$, and suppose one of the elements is pentagon as shown in Fig. 1.The weak form of the boundary value problem of this pentagon element K is given as

\begin{equation} \small

a^K\left ( \boldsymbol{u}^K, \boldsymbol{v}^K \right ) = \int_{\boldsymbol{\Omega}^K} \boldsymbol{\sigma\left ( \boldsymbol{u}^K\right )}:

\boldsymbol{\epsilon\left ( \boldsymbol{v}\right )} d\boldsymbol{\Omega}^K = f^K \left( \boldsymbol{v}^K \right )=

\int_{\partial\boldsymbol{\Omega}^K} \boldsymbol{v}^K \cdot \boldsymbol{t} d\partial\boldsymbol{\Omega}^K,\ \forall \boldsymbol{v}^K\in V\left(K\right) \times V\left(K\right)

\tag{1}

\end{equation}

where in Eq.(1) $ a^K $ and $ f^K $ are the bilinear and linear form defined in the element K; $ \boldsymbol{\sigma} $ and $ \boldsymbol{\epsilon} $ are the stress and strain tensors, respectively, and $ \boldsymbol{v} $ is the test vector-value function which belongs to the local Sobolev space $ V(K)\times V(K) $ defined within the element K; $ \boldsymbol{u} $ is the solution of vector-value function to be found, typically the displacement vector in x- and y-directions; $ \boldsymbol{\Omega}^K $ is the element domain and $ \boldsymbol{\partial\Omega}^K $ is the corresponding Neumann boundary of element K.

FIG.1: DOFs of second-order VEM on pentagon element K

Generally the solution $ \boldsymbol{u} $ is approximated by a function in the subspace of $ V_h(K)\times V_h(K) \subseteq V(K)\times V(K) $ called local virtual element space (or say, local shape function space), and the number of basis functions (shape functions) that span $ V_h(K)\times V_h(K) $ is equal to the number of degrees of freedom (DOFs) of element K defined in the following. Let the element in $ V_h(K)\times V_h(K) $ denote as $ \boldsymbol{v}_h $, the the vector-value function $ boldsymbol{v}_h $ in second-order VEM has the following properties:

- $ \boldsymbol{v}_h $ is continuous on the boundary of element K

- $ \boldsymbol{v}_h $ is a vector with second-order polynomial components on each edge of element K

- $ \Delta \boldsymbol{v}_h $ is a vector with second-order polynomial components on each edge of element K

- The values of $ \boldsymbol{v}_h $ at the 5 vertices of element K

- The values of $ \boldsymbol{v}_h $ at the 5 midpoints of 5 edges of element K

- The two moments of $ \boldsymbol{v}_h $ with respect to the constant vectors $ \boldsymbol{p}_1=[1,0]^T $ and $ \boldsymbol{p}_2=[0,1]^T $ in element K, that is \begin{equation} \small \frac{1}{\lvert \boldsymbol{\Omega}^K \rvert} \int_{\boldsymbol{\Omega}^K} \boldsymbol{v}_h \cdot \boldsymbol{p}_1 d\boldsymbol{\Omega}^K; \quad \frac{1}{\lvert \boldsymbol{\Omega}^K \rvert} \int_{\boldsymbol{\Omega}^K} \boldsymbol{v}_h \cdot \boldsymbol{p}_2 d\boldsymbol{\Omega}^K \tag{2} \end{equation}

- Property 1: $ \boldsymbol{\varphi}_i(1,2,...,22) $ is a second-order polynomial on the element edge;

- Property 2: $ \boldsymbol{\varphi}_i(1,2,...,22) $ satisfies the Kronecker-delta property, that is, for the jth DOF of element K we have $ {\rm dof}_j\left( \boldsymbol{\varphi}_i \right ) = \delta_{ij},\ i,j=1,2,...,22 $

Similar to classical Galerkin finite element method (FEM), the entry of local stiffness matrix $ \boldsymbol{k}^K $ of element K is calculated as

\begin{equation} \small

\left (\boldsymbol{k}^K \right)_{ij} = a^K \left ( \boldsymbol{\varphi}_i, \boldsymbol{\varphi}_j \right )=

\int_{\boldsymbol{\Omega}^K} \boldsymbol{\sigma}\left ( \boldsymbol{\varphi}_i \right ) : \boldsymbol{\epsilon}\left ( \boldsymbol{\varphi}_j \right )

d\boldsymbol{\Omega}^K, \quad {\rm for}\ i,j=1,2,...,22

\tag{4}

\end{equation}

where the subscripts ij indicate the location of entry in $ \boldsymbol{k}^K $. Now comes the most important part of VEM: define a projector

$ {\rm \Pi}^\nabla: V_h(K)\times V_h(K) \rightarrow P^2 \times P^2 $ which maps the function $ \boldsymbol{v}_h $ in the space $ V_h(K)\times V_h(K) $

onto the second-order polynomial space $ P^2 \times P^2 $ satisfying the following orthogonality condition:

\begin{equation} \small

a^K \left ( \boldsymbol{p}_\alpha, {\rm \Pi}^\nabla \boldsymbol{v}_h - \boldsymbol{v}_h \right ) = 0, \quad

{\rm for}\ \forall \boldsymbol{p}_{\alpha} \in P_2 \times P_2\ {\rm and}\ \boldsymbol{v}_h \in V_h \times V_h

\tag{5}

\end{equation}

where $ \boldsymbol{p}_{\alpha} $ are the polynomial basis functions that span the second-order polynomial space $ P_2 \times P_2 $. Then Eq.(4) is reformulated by using the projector $ \Pi^\nabla $ as

\begin{equation} \small

\begin{split}

\left (\boldsymbol{k}^K \right)_{ij} &= a^K \left ( \Pi^\nabla\boldsymbol{\varphi}_i + \left ( \boldsymbol{\varphi}_i - \Pi^\nabla\boldsymbol{\varphi}_i \right ),

\Pi^\nabla\boldsymbol{\varphi}_j + \left ( \boldsymbol{\varphi}_j - \Pi^\nabla\boldsymbol{\varphi}_j \right ) \right ) \\\\

&=\underbrace{a^K \left ( \Pi^\nabla\boldsymbol{\varphi}_i,\Pi^\nabla\boldsymbol{\varphi}_j \right )}_{\rm consistency} +

\underbrace{a^K \left ( \boldsymbol{\varphi}_i - \Pi^\nabla\boldsymbol{\varphi}_i, \boldsymbol{\varphi}_j - \Pi^\nabla\boldsymbol{\varphi}_j \right )}_{\rm stability}

= \left (\boldsymbol{k}_c^K \right)_{ij} + \left (\boldsymbol{k}_s^K \right)_{ij}

\end{split}

\tag{6}

\end{equation}

where $ \Pi^\nabla \boldsymbol{\varphi}_i=\sum_{\alpha=1}^{12} S_{i,\alpha} \boldsymbol{p}_\alpha,\ \boldsymbol{p}_\alpha \in P^2\times P^2 $ is the image of basis function

$ \boldsymbol{\varphi}_i $ projected on the second-order polynomial space which is a linear combination of polynomial basis functions $ \boldsymbol{p}_{\alpha} $ with coefficients $ S_{i,\alpha} $, and $ \left ( \boldsymbol{k}^K \right )_{ij} $ can be thus considered as the sum of consistency term $ \left ( \boldsymbol{k}_c^K \right )_{ij} $ and stability term $ \left ( \boldsymbol{k}_s^K \right )_{ij} $ as shown in Eq.(6).

Based on the defination of projector $ \Pi^\nabla $ and linearity of the stain tensor, the component-wise consistency term $ \left ( \boldsymbol{k}_c^K \right ) $ can be obtained explicitly as \begin{equation} \small \begin{split} \left ( \boldsymbol{k}_c^K \right ) &= \int_{\Omega^K} \boldsymbol{\sigma} \left ( \Pi^\nabla \boldsymbol{\varphi}_i \right ): \boldsymbol{\epsilon} \left ( \Pi^\nabla \boldsymbol{\varphi}_j \right ) d\Omega^K = \int_{\Omega^K} \boldsymbol{\sigma} \left ( \sum_{\alpha=1}^{12} S_{i,\alpha} \boldsymbol{p}_{\alpha} \right ): \boldsymbol{\epsilon} \left ( \sum_{\beta=1}^{12} S_{j,\beta} \boldsymbol{p}_{\beta} \right ) d\Omega^K \\\\ &= \sum_{\alpha=1}^{12} \sum_{\beta=1}^{12} S_{i,\alpha}S_{j,\beta} \int_{\Omega^K} \boldsymbol{\sigma} \left ( \boldsymbol{p}_{\alpha} \right ): \boldsymbol{\epsilon} \left ( \boldsymbol{p}_{\beta} \right ) d\Omega^K = = \sum_{\alpha=1}^{12} \sum_{\beta=1}^{12} S_{i,\alpha}S_{j,\beta}a^K \left ( \boldsymbol{p}_{\alpha}, \boldsymbol{p}_{\beta} \right ) \\\\ &= \sum_{\alpha=1}^{12} \sum_{\beta=1}^{12} \boldsymbol{\Pi}_{i\alpha} \boldsymbol{\Pi}_{\beta j} \boldsymbol{G}_{\alpha \beta} = \left ( \boldsymbol{\Pi}^T \boldsymbol{G} \boldsymbol{\Pi} \right )_{ij}, \quad {\rm for}\ i,j=1,2,...,12 \end{split} \tag{7} \end{equation} where $ \boldsymbol{\Pi} $ is the matrix representation of projector $ \Pi^\nabla $, and matrix $ \boldsymbol{G} $ is defined with entry $ \boldsymbol{G}_{\alpha \beta} = a^K \left ( \boldsymbol{p}_{\alpha},\ \boldsymbol{p}_{\beta} \right )$.

As for the stability term $ \left ( \boldsymbol{k}_s^K \right )_{ij} $ of element K, fistly define a 22-by-12 matrix D with entry as \begin{equation} \small \boldsymbol{D}_{i\alpha} = {\rm dof}_i \left ( \boldsymbol{p}_{\alpha} \right ) \quad {\rm for} i=1,2,...,22\ {\rm and}\ \alpha=1,2,...,12 \tag{8} \end{equation} Next, by decomposing the image of projection $ \Pi^\nabla \boldsymbol{\varphi}_i $ by the vector-valued functions in the local virtual element space $ V_h \times V_h $, we can have the following matrix representation of another projection $ \overline{\Pi}^\nabla: V_h \times V_h \rightarrow V_h \times V_h $ which maps the function in space $ V_h \times V_h $ onto itself \begin{equation} \small \overline{ \boldsymbol{\Pi} }_{ij} = {\rm dof}_i \left ( \Pi\nabla \boldsymbol{\varphi}_j \right ) = {\rm dof}_i \left ( \sum_{\beta=1}^{12} S_{j,\beta} \boldsymbol{p}_{\beta} \right ) = \sum_{\beta=1}^{12} \boldsymbol{D}_{i \beta} \boldsymbol{\Pi}_{\beta j} = \left( \boldsymbol{D} \boldsymbol{\Pi} \right )_{ij} \quad {\rm for}\ i,j = 1,2,...,22 \tag{9} \end{equation} where $ \overline{\boldsymbol{\Pi}} $ is the matrix representation of projection $ \overline{\Pi}^\nabla $. Based on Eq.(9), the stability term $ \left ( \boldsymbol{k}_s^K \right )_{ij} $ is calculated as \begin{equation} \small \left ( \boldsymbol{k}_s^K \right ) = \gamma \tau^* \left ( \boldsymbol{I} - \overline{\boldsymbol{\Pi}}_i^T \right ) \left ( \boldsymbol{I} - \overline{\boldsymbol{\Pi}}_j \right ) \quad {\rm for}\ i,j = 1,2,...,22 \tag{10} \end{equation} where $ \boldsymbol{I} $ is the 22-by-22 identity matrix;$ \gamma $ is the user-defined parameter which can be chosen as 1 for elastic problem, and $ \tau* $ can be calculated by various formulas, such as $ \tau^*={\rm trace} (\boldsymbol{k}_c^K ) $. Hence, through Eqs.(1) to (10), one can calculate all the entries in local stiffness matrix $ \boldsymbol{k}^K $ of element K, and the global stiffness matrix can be obtained by assembling all the local stiffness matrices in the same manner as the classical Galerkin FEM.

Based on the defination of projector $ \Pi^\nabla $ and linearity of the stain tensor, the component-wise consistency term $ \left ( \boldsymbol{k}_c^K \right ) $ can be obtained explicitly as \begin{equation} \small \begin{split} \left ( \boldsymbol{k}_c^K \right ) &= \int_{\Omega^K} \boldsymbol{\sigma} \left ( \Pi^\nabla \boldsymbol{\varphi}_i \right ): \boldsymbol{\epsilon} \left ( \Pi^\nabla \boldsymbol{\varphi}_j \right ) d\Omega^K = \int_{\Omega^K} \boldsymbol{\sigma} \left ( \sum_{\alpha=1}^{12} S_{i,\alpha} \boldsymbol{p}_{\alpha} \right ): \boldsymbol{\epsilon} \left ( \sum_{\beta=1}^{12} S_{j,\beta} \boldsymbol{p}_{\beta} \right ) d\Omega^K \\\\ &= \sum_{\alpha=1}^{12} \sum_{\beta=1}^{12} S_{i,\alpha}S_{j,\beta} \int_{\Omega^K} \boldsymbol{\sigma} \left ( \boldsymbol{p}_{\alpha} \right ): \boldsymbol{\epsilon} \left ( \boldsymbol{p}_{\beta} \right ) d\Omega^K = = \sum_{\alpha=1}^{12} \sum_{\beta=1}^{12} S_{i,\alpha}S_{j,\beta}a^K \left ( \boldsymbol{p}_{\alpha}, \boldsymbol{p}_{\beta} \right ) \\\\ &= \sum_{\alpha=1}^{12} \sum_{\beta=1}^{12} \boldsymbol{\Pi}_{i\alpha} \boldsymbol{\Pi}_{\beta j} \boldsymbol{G}_{\alpha \beta} = \left ( \boldsymbol{\Pi}^T \boldsymbol{G} \boldsymbol{\Pi} \right )_{ij}, \quad {\rm for}\ i,j=1,2,...,12 \end{split} \tag{7} \end{equation} where $ \boldsymbol{\Pi} $ is the matrix representation of projector $ \Pi^\nabla $, and matrix $ \boldsymbol{G} $ is defined with entry $ \boldsymbol{G}_{\alpha \beta} = a^K \left ( \boldsymbol{p}_{\alpha},\ \boldsymbol{p}_{\beta} \right )$.

As for the stability term $ \left ( \boldsymbol{k}_s^K \right )_{ij} $ of element K, fistly define a 22-by-12 matrix D with entry as \begin{equation} \small \boldsymbol{D}_{i\alpha} = {\rm dof}_i \left ( \boldsymbol{p}_{\alpha} \right ) \quad {\rm for} i=1,2,...,22\ {\rm and}\ \alpha=1,2,...,12 \tag{8} \end{equation} Next, by decomposing the image of projection $ \Pi^\nabla \boldsymbol{\varphi}_i $ by the vector-valued functions in the local virtual element space $ V_h \times V_h $, we can have the following matrix representation of another projection $ \overline{\Pi}^\nabla: V_h \times V_h \rightarrow V_h \times V_h $ which maps the function in space $ V_h \times V_h $ onto itself \begin{equation} \small \overline{ \boldsymbol{\Pi} }_{ij} = {\rm dof}_i \left ( \Pi\nabla \boldsymbol{\varphi}_j \right ) = {\rm dof}_i \left ( \sum_{\beta=1}^{12} S_{j,\beta} \boldsymbol{p}_{\beta} \right ) = \sum_{\beta=1}^{12} \boldsymbol{D}_{i \beta} \boldsymbol{\Pi}_{\beta j} = \left( \boldsymbol{D} \boldsymbol{\Pi} \right )_{ij} \quad {\rm for}\ i,j = 1,2,...,22 \tag{9} \end{equation} where $ \overline{\boldsymbol{\Pi}} $ is the matrix representation of projection $ \overline{\Pi}^\nabla $. Based on Eq.(9), the stability term $ \left ( \boldsymbol{k}_s^K \right )_{ij} $ is calculated as \begin{equation} \small \left ( \boldsymbol{k}_s^K \right ) = \gamma \tau^* \left ( \boldsymbol{I} - \overline{\boldsymbol{\Pi}}_i^T \right ) \left ( \boldsymbol{I} - \overline{\boldsymbol{\Pi}}_j \right ) \quad {\rm for}\ i,j = 1,2,...,22 \tag{10} \end{equation} where $ \boldsymbol{I} $ is the 22-by-22 identity matrix;$ \gamma $ is the user-defined parameter which can be chosen as 1 for elastic problem, and $ \tau* $ can be calculated by various formulas, such as $ \tau^*={\rm trace} (\boldsymbol{k}_c^K ) $. Hence, through Eqs.(1) to (10), one can calculate all the entries in local stiffness matrix $ \boldsymbol{k}^K $ of element K, and the global stiffness matrix can be obtained by assembling all the local stiffness matrices in the same manner as the classical Galerkin FEM.